Introduction

Everyone that has ever shopped for a pair of sunglasses knows the struggle of that process. Shoppers try out tens of pairs, take equally as many selfies of themselves with the glasses and swipe desperately from left to right to compare them against each other to find the best pair. To make this easier and involve salespeople in this process, Nordstrom, a Fortune 500 company and one of the leading American luxury store chains, sent their Innovation Lab, an interdisciplinary team consisting of programmers, designers and ethnographers, tasked with keeping Nordstrom relevant in the digital age, on a one-week assignment. The mission, developing an iPad app which allows shoppers to easily take selfies with different sunglasses and compare them against each other, was relatively normal. The setting, however, was anything but that. The whole app was built on the shopping floor of the biggest store Nordstrom had to offer.

The Start

The team started only with the simple input “People take a lot of pictures of themselves with the sunglasses, I’d be cool to show them side by side to make the process better”. From there on out the team chose to create an iPad app which customers and salespeople alike could use to do this in Nordstrom stores. To only develop features end users wanted to use and never work on something that would not create value the team chose to develop the app with direct user feedback. And what space is better suited to get feedback from end users than the place where these end users are? Thus, the decision was made to develop the app in a one-week “Flash Build” in the biggest Nordstrom store worldwide.

Before any development could start, the team built a User-Story-Map, a tool which teams use to visualize the journey a customer takes with a product. In Nordstrom’s case, the team mapped all the steps a customer takes to buy a pair of sunglasses. Based on this they asked themselves how that process would change with their app and derived from this the features the app would have to provide to change the process in this way.

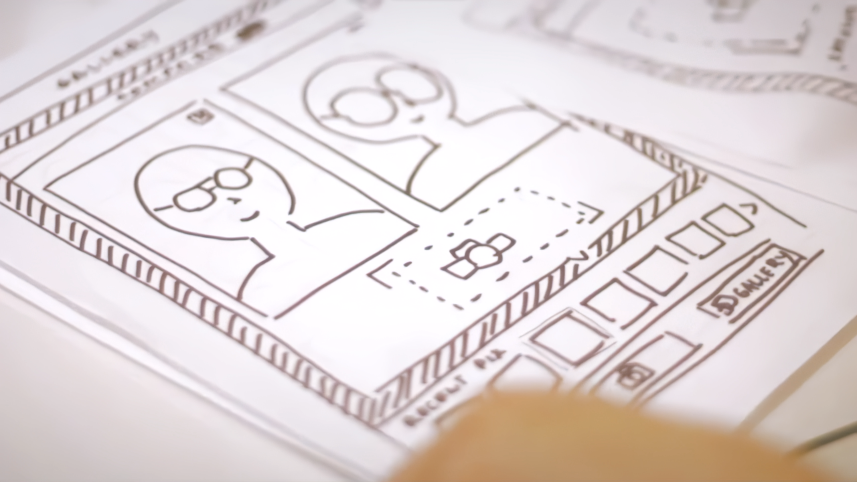

After laying the foundations of the app, the team obviously wasn’t ready to provide users with a usable app. Instead, they opted to show customers so-called “paper prototypes” to rapidly test user interface (UI) concepts and feature ideas. A paper prototype is exactly what one would imagine under that term. The team’s user experience specialist went up to customers with a stack of papers with different UI states drawn onto them. The customers could then use these paper slides as they would the final app with the user experience specialist swapping different pieces of paper in and out for each action the customer takes. This technique allowed the development team to prototype features and get first valuable feedback quickly at the cost of a few sheets of paper.

Development

On the second day, the development team had already built a minimum viable product which could be tested among the customers and salespeople in the store. The location of the development team on the store floor led to a very fast feedback cycle. After a couple of features were completed, the team could just compile the app, load it onto an iPad and switch it with the iPad which was currently used for testing. Instead of the usual focus testing, the results of which can take weeks to come back to the development team, the Nordstrom development team received feedback for their new features in ten minutes or less after completing them. This instant feedback led to a lot of new, user-requested, features being added during the week. When salespeople in the store mentioned, that the breadth of pictures being taken made it hard to remember which photo was connected to which pair of sunglasses, the development team built a feature which allowed photos to be given names. When users did not understand that pictures showed up in another spot when tapped, the team built animations which showed the connection between the two views. Besides new features being added the customers also helped the development team to find critical bugs which otherwise probably would not have been found for months. An example of this is an issue which caused certain sunglasses to show up as black due to the polarization from the iPad camera and the sunglasses cancelling each other out. To solve this Nordstroms team simply converted the app to landscape mode.

Result

Even though the app was completed at the end of the day and the general sentiment among the team and salespeople in the store was positive, the project ultimately failed and the app was never rolled out across Nordstrom stores. The main reason the app failed was, that it did not properly address customer needs. This problem originated even before work on the app started. In a post-mortem analysis, the team concluded, that one of the main problems was, that the idea for the app originated with the sales department and not from observing normal customers. This combined with the fact that the salespeople in Nordstroms Seattle Store were better at articulating their needs than the customers led to the final app being heavily skewed towards the perspective and needs of salespeople.

However, the failure of the project was not necessarily a bad thing. The failure to properly assess customer needs led the team to explore new methods to better capture these in future experiments. Furthermore, the team started using the Desirability, Feasibility, Viability (DFV) framework to assess future projects. This method tries to ensure that an idea is needed by the customer (Desirability), possible to create (Feasibility) and has a profitable business model (Viability). The team would be tasked with exploring ideas which had uncertainty in any of these fields, validating if they fulfilled the DFV-Framework and if they did, delivering the idea as a product as fast as possible to end users. Furthermore, instead of avoiding future failure through safer projects, Nordstroms Innovation Lab even set itself an 80% failure target rate to force itself to always innovate. In the coming years, the Innovation Lab applied this knowledge to projects like a wedding mood board, not unlike the then obscure Pinterest and TextStyle, an app which allowed customers to shop via SMS messages. In 2015 the Innovation Lab was shrunk drastically, with most of its employees being absorbed into other experiment and innovation-focused parts of the company.

Sources

Nordstrom Innovation Lab (2011), https://vimeo.com/274897152, accessed on 02.04.2023

CC24 (2015), https://d3.harvard.edu/platform-digit/submission/nordstrom-innovation-lab-rethinking-how-you-shop/, accessed on 11.04.2023

Grossman-Kahn, B., & Ryan, R. (2012, 11 12). Skip the Silver Bullet: Driving Innovation through Small Bets. Leading Innovation through Design Proceeding of the DMI 2012 International Research Conference Boston, USA 8–9 August 2012, pp. 815-829

Tricia Duryee (2015), https://www.geekwire.com/2015/nordstrom-shrinks-innovation-lab-reassigns-employees-shakeup-tech-intiatives/, accessed on 11.04.2023

Christine Kern (2015), https://www.retailsupplychaininsights.com/doc/nordstrom-hopes-to-win-over-shoppers-with-text-and-buy-program-0001, accessed on 16.04.2023

IDEO U (2017), https://www.ideou.com/blogs/inspiration/how-to-prototype-a-new-business, accessed on 17.04.2023

Before any development could start, the team built a User-Story-Map, a tool which teams use to visualize the journey a customer takes with a product. In Nordstrom’s case, the team mapped all the steps a customer takes to buy a pair of sunglasses. Based on this they asked themselves how that process would change with their app and derived from this the features the app would have to provide to change the process in this way.